Paper: Decreased Virtual Water Outflows from the Yellow River Basin Are Increasingly Critical to China

Abstract

Water scarcity is an emerging threat to food security and socio-economic prosperity, and it is crucial to assess crop production response to water scarcity in large river basins. The water footprint, which considers water use in supply chains, provides a powerful tool for assessing the contributions of water resources within a certain region by tracking the volume and structure of virtual water flows. In this study of the structure of the water footprint network from a complexity perspective, we reassessed the significance of water resources for crop services in a large river basin with a severe water shortage – the Yellow River basin (YRB) of China. The temporal increase of the complexity index indicated that the virtual water outflows (VWFs) from the YRB were becoming increasingly critical to China; i.e. the ability of YRB to produce crops boosted the difficulty of its water being replaced by water exporting from other basins. Decomposition of complexity suggested that during the 1980s to 2000s, the temporally increased complexity was due mainly to the lack of competitors and the increasing uniqueness of crops supporting VWFs. This complexity deeply embedded the YRB into the footprints of a water network that facilitated further development with constrained water resources. Still, it also reinforced reliance from other regions on YRB’s scarce water. Based on this analysis, we suggest that resource regulation should be carried out appropriately to ensure ecological sustainability and high-quality development of river basins.

Brief Introduction

The water footprint and virtual water (Conference on Priorities for Water Resources Allocation and Management, 1993), a geographically explicit indicator that involves water use in supply chains, has provided a powerful tool for assessing the contribution of water resources to a basin and tracking the transfer of water resources across regions (Jaramillo and Destouni, 2015; Oki and Kanae, 2004). Virtual water can be associated with specific products that transfer through complex trade relationships between geographic units (Hoekstra, 2014). Virtual water trade networks consist of virtual water outflows (VWFs) that are embedded in production and consumption trajectories of crops (Oki and Kanae, 2004; Chini et al., 2018; Bae and Dall’erba, 2018). For example, the VWF from China’s water-rich south to its water-scarce north has been quantified, and the network represented by crop trade between provinces has been mapped (Zhai et al., 2019; Zhuo et al., 2016a). However, because these volume-based studies have ignored the complexity of crop supply and demands (linked with trade) and the uniqueness of each basin (determined by regional characteristics), they have failed to consider the structure of water footprint networks. The structure of a water footprint network reflects the inherent heterogeneity of the distribution of the resources and the pattern of production and consumption. This heterogeneity is consistent with the fact that a water resource cannot be simply replaced by the same volume of water in another basin (Yu and Ding, 2021; Zhuo et al., 2016a; Li et al., 2020). This replacement problem reflects that water is not the only resource needed for widely circulated agricultural products. Because of path dependence, others resources, such as the unique hydrothermal conditions and the status of infrastructure within a basin, all determine the position of the basin (or a region) in a water footprint network (Best, 2019). Complexity, a rapidly developing concept in fields of study such as complexity science, network science, and development economics, represents the “capacity” that is embedded in a certain region, based on measurement of its position in structural terms (Hidalgo, 2021; Arthur, 2021; Meng et al., 2020; Hidalgo et al., 2007). For water resources that are unevenly distributed geographically, complexity can characterize a basin’s overall capacity to provide water services required for national crop production. Because complexity-based metrics have been extensively studied in the empirical assessment of economic vitality through a bipartite-networks approach, the concept of complexity should be taken into consideration in the context of water footprint networks to upgrade the toolbox used for integrated water resources management (Hidalgo, 2021; Hidalgo and Hausmann, 2009; Liu et al., 2017). With such a toolbox, the regional significance of the water supply services provided by the basin through agricultural production can be comprehensively reassessed in a way that takes into account structural factors (Fig. 1).

Main Results

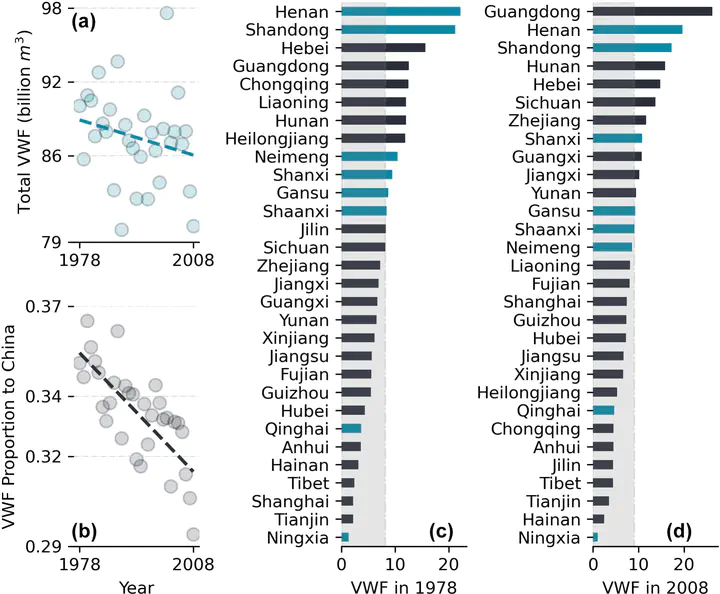

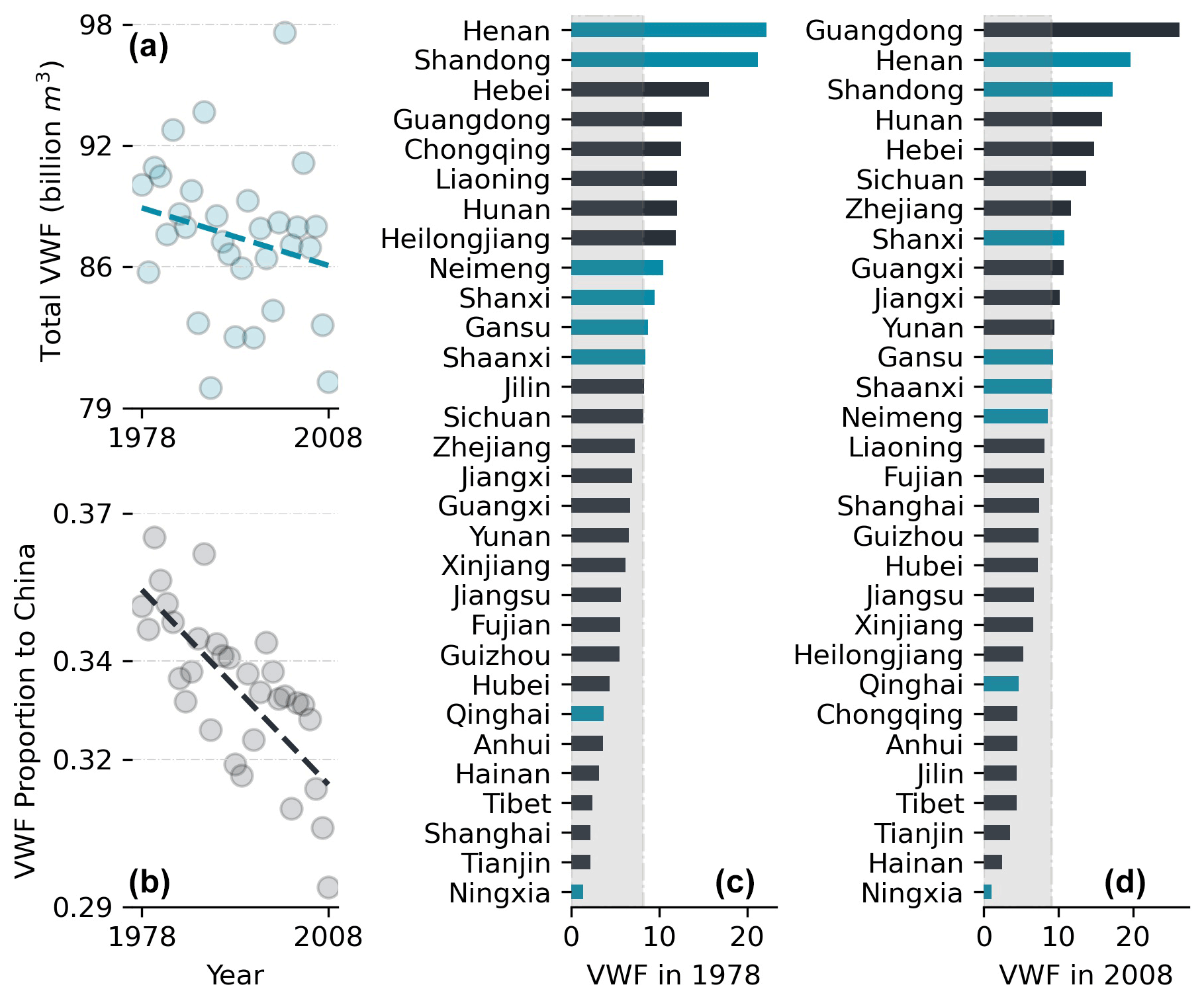

The total volume of virtual water outflows from the provinces in the YRB decreased continuously during the study period (Fig. 2a), and its proportion of the national total decreased by an even more significant percentage (Fig. 2b). In 1978, there were five provinces in the YRB whose virtual water outflows (VWF) exceeded the national average, but there were only three of them in 2008, and their overall ranking had decreased significantly. Though the total volume, share, and ranking of VWF across provinces of the YRB were all decreasing, the average complexity index of the YRB was holistically higher than that of China (Fig. 3a). The gap between the two increased rapidly after 1985. It reached its widest point in 1993 when the average complexity index of the YRB was about 1.4 times the national average (Fig. 3b). After then, the difference between the two decreased with some fluctuations, but the complexity of the YRB remained about 1.2 times the national average (Fig. 3b).

Discussion: reasons of changing complexity

The use of regional VWF, especially within a water footprint network, has been a common approach to assess the importance of water resources, but complex structures have not been comprehensively evaluated in these assessments (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2020, 2011; Fang et al., 2014). The Yellow River, an agriculture-oriented basin with substantial heterogeneity in the upper, middle, and lower reaches, has scarce water resources that are the cornerstone of its crop production (Wang et al., 2019). With “The Reform and Opening” of China since 1978, domestic crop trades have gradually increased both in diversity and the volume, and that increase may have caused the total VWF volume to keep increasing. At the same time, however, the YRB was the first basin to apply a water allocation scheme because extreme water shortages caused the river to frequently dry after the 1970s (Wang et al., 2019). Therefore, during the time that the national VWF was transferred mainly from the north (where the YRB is located) to the south (Zhuo et al., 2016b), the contribution of the YRB, which is deficient in water resources, decreased in volume (Fig. 2).

However, considering the structure of the crop–water footprint bipartite network, that did not indicate the YRB had been decreasing in importance to China. On the contrary, our complexity-based analysis revealed the differences in complexity between the YRB and China since 1978. As a result, the YRB’s water footprints have been complex for other basins to replace crop production. Our decomposition results suggested that this difficulty was due mainly to a low number of competitors and the increasing uniqueness of crops supporting VWF from the YRB. The Yellow River is a large river that crosses an arid, semi-arid, and monsoon climate zone. The small number of competitors and the relatively high uniqueness of the YRB depend partially on the unique geographical conditions in the YRB (Fu et al., 2017). For example, high-quality apples produced in the fertile but arid Loess Plateau in the middle reaches of the YRB and the wet areas in the lower reaches together account for more than 90 % of the total apple production in China regions, which can compete with the YRB. The increasing uniqueness of the YRB means that its ability to improve the quality of its agricultural products and push competitors out of the crop supply network is growing. Those regions that can compete with a particular crop from the YRB (such as Xinjiang, which also exports many high-quality apples) are limited by an extreme shortage of water resources and cannot increase diversification, hence lacking overall competitiveness.

Discussion: future applications of Virtual water complexity

Assessing the value of natural resources has been a constant problem because of the trade-off between economic efficiency, social equity, and resource availability (Dalin et al., 2015; Grafton et al., 2018; Yoon et al., 2021). The “Porter hypothesis” of the environment has proposed that environmental regulation can stimulate technological innovation. Similarly, the stimulus of resource scarcity can improve optimization of a market allocation for efficient use of resources (Wagner, 2004; Luptáčik, 2010). The complexity of the YRB had risen above the national average since about 1987, when the river basin was regulated. Because of water scarcity, the Chinese government required provinces to adhere to strict resource quotas (Wang et al., 2018). During this period, although the total VWF of the YRB and its proportion decreased, the increasing complexity indicated that the resource-constrained YRB was gaining market advantages. In different ways, this advantage has manifested itself as an increase of the position of the YRB in the virtual water network and by an increase of both competitiveness and uniqueness (Fig. 4) (Fang and Chen, 2015; Fang et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2012). After the 1990s, the complexity index of China evidenced a similar trend of improvement, which was concomitant with the period when the strict control of water resources and a transformation to water conservation were implemented throughout the whole country (Zhou et al., 2020; Liu and Yang, 2012).

According to the literature (Zhou et al., 2020), the slowdown of the growth of China’s water consumption can be divided into two stages by the 1990s. While growth during the earlier period occurred mainly in arid and semi-arid areas (e.g. the YRB), growth during the latter period affected the whole country. Therefore, the increase of the national average level of complexity lagged behind that of the YRB. This lag was probably the result of the rest of China pursuing structural advantages later than the YRB. Traditional development economic theory points out that the use of resources with comparative advantage is a prerequisite for producing an economically efficient division of labour and a marketing network (Hidalgo and Hausmann, 2009). In this case, however, before water resources are severely restricted, it may not be more cost-effective to intensify a comparative advantage than to expand resource investment. This conclusion is consistent with the theories related to the “peak water use” and the “efficiency paradox” (Gleick and Palaniappan, 2010; Grafton et al., 2018). Thus, the complexity index may depict the process by which the YRB and then China pursued this structural advantage within the water footprint network as constrained by resources.

Conclusion

This paper took the structure of the water footprint network from a complexity perspective. It assessed the significance of water resources for crop services in a large river basin with a severe water shortage – the Yellow River basin (YRB). From 1978 to 2008, the number of virtual water flows (VWFs) from the YRB and its percentage of the total VWF from the national total decreased significantly. The fact that the YRB has lagged behind the national VWF trend is probably related to restricted water use policies. However, our results showed that the complexity of the YRB increased and was significantly higher than the national average during the period from the 1980s to the 2000s. Decomposition of complexity suggested that this pattern was due mainly to few competitors and the increasing uniqueness of supporting VWF crops for the YRB. Based on an assessment of water conservation policies in China, we suggested that the initial promulgation of resource regulations was the key to a competitiveness-oriented transformation for crop production in the YRB. Subsequently, the increased complexity enabled the YRB to develop with limited water resources. However, it also more deeply embedded the YRB into water footprint networks where scarce water cannot be easily replaced. From the complexity analysis, we point out that resource regulation should be carried out at an appropriate stage to ensure ecological sustainability and high-quality development of river basins.

Related

Post: Plain introduction: Complexity, another dimension of virtual water

Supplementary notes can be added here, including code, math, and images.