Improving Representation of Collective Memory in Socio-hydrological Models and New Insights into Flood Risk Management

Summary

Collective memory plays a controlling role in adaptation to potential flood risks, by learning from past disasters. However, with little quantitative empirical data, previous socio-hydrological models have conceptualized the decaying process of flood memory in an oversimple approach. Based on survey data, we suggest that using the Universal Decay Model (UDM) proposed by previous researchers provides better fitting results for the decay of flooding memory. Then, significantly reduced losses for the same flood sequence were predicted by integrating the UDM into a sociohydrological model by 16% and the differences between different clusters (urban and rural respondents) can even reach 22.81%. These differences suggest that previous socio-hydrological models have been too simplistic in their conceptualizations of decaying processes associated with collective memory, which may have limited deeper insights into flood risk management.

Brief Introduction

Collective memory (or social memory), a concept representing the collective perception of events and shared experiences (Assmann & Czaplicka, 1995), may determine the capacity of communities to maintain awareness of specific risks (Viglione et al., 2014). One of the significant consequences of future climate change is a predicted increased incidence of flood hazards (Arnell & Gosling, 2016; Jaramillo & Destouni, 2015; Winsemius et al., 2016). In the face of increasing flood risks on the world’s largest rivers and their floodplains, collective memory plays a controlling role on how society keeps awareness of flood risk, by learning from past disasters (Best, 2019; Blöschl et al., 2017; Fanta, Šálek, & Sklenicka, 2019).

Based on a survey regarding five well-documented historical floods in Ningxia Floodplain, China, we test how flooding memory decays and integrate it into the socio-hydrological models. Then, by comparing different simulation results, we explore if any essential difference raised after reconstructing the society modules with the UDM. Lastly and more importantly, we give discussions on how these differences inspire further insights on flood risk managements.

Main Results

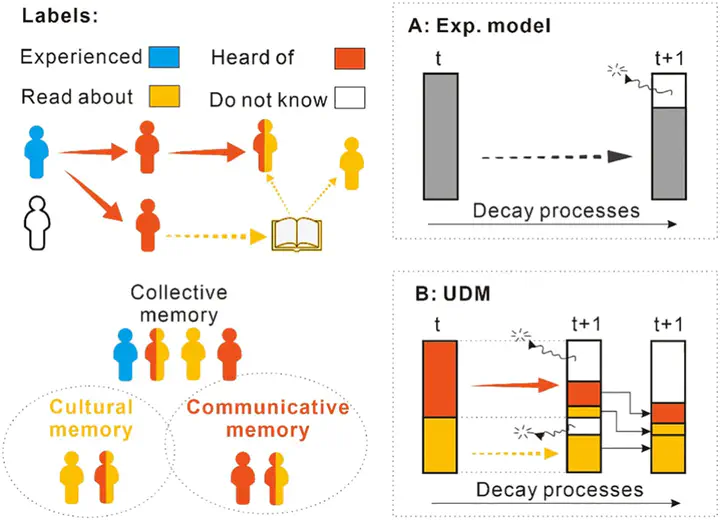

In our survey, respondents’ memory to five well-documented major floods were collected. Once admitted to having memory to a certain historical flood, respondents must recall how they get known about it. Then, we labelled their answers by “heard of”, “read about” or “experienced”. Then, we assumed that the “heard of” label corresponds to communicative memory, the “read about” label corresponds to cultural memory, and the “experienced” label corresponds to that who initially influenced (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Respondent labels and their correspondence to different model variables. (A) Decay processes of collective memory according to an exponential model. (B) Decay processes of communicative memory and cultural memory, with part of communicative memory transfer into cultural one at the same time

Based on those data, we examined two decay models of collective flooding memory: the original exponential model and the UDM (where communication memory and cultural memory are split based on collective memory theory, see the paper for details.) Our results suggest that for all types of dataset, the UDM throughout provides an effective fitting, as the adjusted R2 remained above 0.9. Based on the improved model based on the UDM, our simulations reveals that collective memory is accumulating more rapidly when the UDM-based model using parameters fitted by the urban dataset, and the flooding losses become progressively lower (Figure 8). However, when using parameters fitted by the rural dataset, the change of flooding memory is rather similar to that simulated by exponential-based ones, which have much slower processes for memory accumulation (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Flooding memory simulation (A) and losses simulation (B) under a 100-year potential flood sequence (the same sequence as Figure 6), where different datasets or different memory-decay models (the UDM or the exponential model) were used

Discussion: Why the UDM makes more sense?

- Many theories have depicted a general process of memory decaying, in which the newest and classic ones both point out that collective memory may consist of communicative memory (or living memory) and cultural memory (or distant memory) (Boyer & Wertsch, 2009; Hirst, Yamashiro, & Coman, 2018; Rubin, 2014a, 2014b).

- A large body of literature suggests that collective memory following completely different laws from individual memory, as complex propagations and interactions play a role (Assmann & Czaplicka, 1995; Boyer & Wertsch, 2009; Candia et al., 2019).

Discussion: How can the UDM inspire insights of flood risk management?

- Firstly, the improvement of the society module by the UDM contributes to further development of the related socio-hydrological models.

- Second, integration of the UDM helps in exploring differences between different clusters (e.g., rural and urban dwellers) that are prevalent in the face of flooding risks.

- Finally, for policymakers, models should make practical sense to help in answering the question of how to maintain the flooding memory (Loucks, 2015; Troy, Pavao-Zuckerman, & Evans, 2015).

Conclusion

Collective memory is often cited as an important variable in interplays between society and floods, but previous socio-hydrological models have conceptualized its decay too simply. We examined the real-life flooding memory through a survey and data were used to fit different models for the decay of flooding memory. Our results suggest that the Universal Decay Model (UDM), rather than the exponential model widely adopted in related socio-hydrology models now, provides more consistent interpretations of flood memory. We then integrated the UDM into a socio-hydrological model for further simulations. Once again, results indicate that the UDM-based model successfully captured differences between clusters: Rural dwellers are more likely to suffer larger total flooding losses than urban respondents within a same flooding sequence as urban dwellers can accumulate flood memory more quickly. In summary, the exponential decay model widely used now lacks a sufficiently valid explanation of the social process associated with collective memory. On the other hand, supported by the results of survey, goodness of fit, and differences between models simulations, an integration of the UDM may well inspire us in generating deeper insights into flood risk management. We call for, therefore, a further exploration of socio-flood interactions based on the UDM as a society module in the future.